Rhyme is a way of playing with words

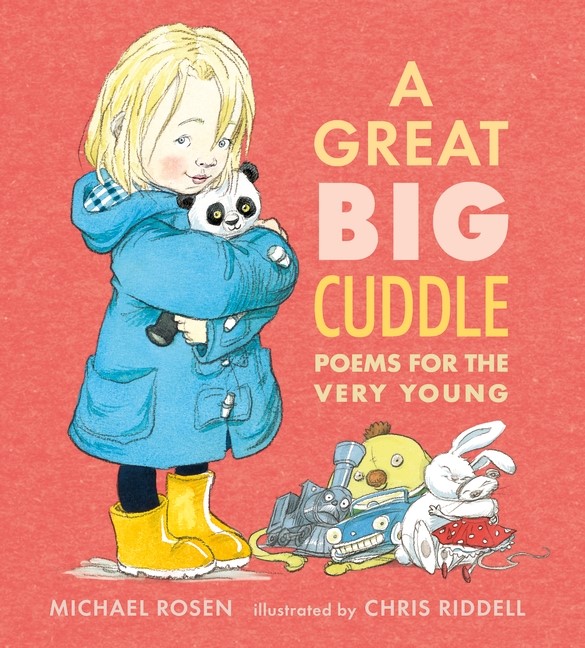

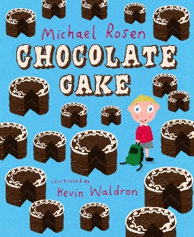

Michael Rosen

When we make two words sound the same, there’s a tiny moment when instead of listening for the meaning, we’re listening to the sounds of the words: less about ‘sense’, more about ‘sound’. This makes rhyme ideal for non-sense – nonsense. It’s also good for jokes. Rhyme does this through setting up expectations. A good deal of humour works from setting something up, and then knocking it down with a surprise.

Think of the most famous joke of all, person walks along the road and falls over. The expectation is that the person will go on walking down the road – but they don’t. Rhyme often does something similar: it sets up an expectation, we start to predict what kind of word is coming, and then it doesn’t. We laugh. Or maybe rhyme will set up an expectation and when the rhyming word comes along, it feels like completing, or ‘closure’ as they said. ‘Closure’ is satisfying to the ear and mind, rather like music when we’re on the major scale and the tune finishes on the ‘tonic’ note, or the ‘doh’ of the scale.

So, rhyme can do all these kinds of jobs for us, and we end up with a sense of pleasure from it. For young children there is the added possibility that it connects them with the ‘physical’ side of language. Sound is ‘physical’ because we make it by exciting atoms and molecules in our throats and ears. Meaning is about our mental apparatus: thought, consciousness, awareness, mind…

Quite a lot of the time, very young children can hear the physical side of language: sound, volume, pitch, speed of talking without fully ‘getting’ the meaning. It’s quite often puzzling. What do all these people on the TV and radio mean? What do parents and grandparents mean when they’re talking to each other.

When we create language that focusses on the physical, I think it connects children to this state of mind they are in where they perceive language as more to do with the physical than the mental, more to do with sound than meaning.

It must be a relief for them to hear ‘vooby, vooby, vooby’ instead of this constant atmosphere of stuff you don’t quite understand. If, for a moment, as with rhyme, it can seen that language is mocking real words, with its echo and chiming effect, then my view is that that’s a relief too. It’s like saying to children, ‘Listen to this and just enjoy the fun of sound and the meaning may or may not come along later.’

Follow lovemybooksUK15

Follow lovemybooksUK15